The young missionary – a peregrini, meaning one on a life-pilgrimage – wore two crosses; but not around his neck nor on his simple, woven robe. The Celtic designs were tattooed onto his eyelids so that, when he slept, the original Cross of Christ was projected from both his sleeping eyes into the world… Truth never sleeps.

A Christ that he had reached out and touched, as though it were his deepest friend…

It was hot, the day he came back to Tain. May was giving way to June, and the weather had changed for the better. For years, the discomfort of the monk’s robe – a white tunic covered by a cowl – had become a thing of the background, not allowed to intrude into his finely trained consciousness. A consciousness filled with the magic of refined thought and the devotion of a mind entirely turned to the good.

In addition to the Scriptures, the Brothers of Ireland had given him everything they had: well structured and beautifully crafted writing in the universal language of Latin; a deep understanding of music and the special numbers that made it harmonic; an observation of the sun and stars so acute that he, even alone, could calculate the correct dates in the cycle of the religious year.

The mind the Irish brothers had bestowed on him was full of ‘knowing’ – his to transform to wisdom – but it was not at the expense of the practical, the how to do…

Soon, if his mission was allowed to take root in this land of his fathers, he would be building a chapel. He had all the necessary skills to transform stone, metal and wood for that purpose; and, beyond that, strong hands as delicate as a feather, when needed.

First, he had to make his tools, but for that he needed the help of a local forge. If his childhood friend, the son of a blacksmith, had survived to adulthood, he hoped to trade an education of the man’s children for the strength of metal.

Ahead of him, now, was the last of the ridges that led to Tain. His leather sandals, made by his own hands, were wet with dew and dirty. His feet were sore from the weeks of walking across Scotland from its west coast fishing village where the tiny boat from Ireland had left him. But it was a joyous pain, and no match for the joy in his heart at smelling the sweet scents of home.

He crested the last rise and stopped, fighting back tears as he looked down on the place whose people he wanted to serve for the rest of his days. The small town of Tain was just waking, the sun climbing on the horizon and painting the calm sea with a line of shimmering gold. This way, it called, as it had a hundred times on his long walk. This way…

———-

This is fiction, but as close to the spirit and facts of St Duthac’s early life as my research has been able to take me.

Duthac was a real figure, yet the details of his life can be elusive. He was born in AD 1000 and died in 1065. Despite devoting his life to Tain, he did not die there. In his final years, something pulled him back to Ireland, presumably to the school of God and Selfless Love that had given him his spiritual wings. In 1253, long after his death, his ‘relics’ – mainly bones – were returned from Ireland by unknown benefactors, to the same tiny chapel he built in Tain.

Much later, the relics were transferred from the abandoned chapel to what is now the St Duthac Memorial Church. Much of St Duthac’s published story is based on the same potted text, some of which is incorrect. It’s an important fact that the ‘relics’ of the saint came back to the original chapel that he had built by hand and where he worked and taught.

St Duthac was one of Scotland’s most revered and well-known saints. The Scottish Reformation, in 1535, brutally erased the saints and their worship, removing all ritual and replacing decoration with plainness. Music was also banned, replaced only with the chanting of psalms.

The memory of St Duthac was removed from history… To the victors, the spoils. The truth of the long human story is constantly altered in this way. Curiously, unlike other saints – such as Columba or St Andrew – Duthac’s name was only ever preserved in Tain, the town he served and loved, and which hosts his name and his works to this day. St Duthac’s relics were later moved within Tain to the first of two churches built in his name. The relics were mysteriously ‘lost’ during the reformation, and never seen again…

Most of his life is lost to history, but much of Duthac’s appeal and status can be inferred from the folk tales that come down to us from ‘his people’. Two of his ‘miracles’ are illustrative of this.

In the first, when a young child, he was asked to transport some ‘blazing coals’ to start another fire. He did so with his bare skin, remaining unburnt. Here we have to look beyond the literal for the meaning. Certain parts of the detail stand out, in the way of such stories:

He was a child – a young soul. His life lay ahead of him, the blazing coals are symbolic of a ‘fire’ that would burn others, yet were not a danger to him. Through the gift of a ‘high nature’ – earned or by birth – he was able to hold and transport that fire. The fire can be read as deep spiritual knowledge; the transportation as teaching. It was a power that was his to transform so that it would inspire, but not burn others. He was the higher vessel. His duty was to use it wisely and to teach those ready to receive.

St Duthac is said to have been of noble birth, yet no records remain to support this. Perhaps this, too, is symbolic, and fits with the above interpretation.

In another of the ‘miracles’, a man asks one of Duthac’s younger disciples to carry a gift of some meat and a gold ring to the saint. The disciple is careless and lets a bird of prey steal them. Arriving, crestfallen, at the chapel, the young man recounts his sorry tale. St Duthac forgives him and summons the eagle. He lets the bird keep the meat, but takes the ring.

The lesson is to cherish the true and perfect ‘gold’ of the ring and let the ‘lower’ – the meat – be left to nature’s cycles of birth, maturity and decay. Duthac’s status (of ‘noble birth’) is one of mastery of nature, i.e. working completely with it. Nature is then content to conform to this ‘noble’ human will. The Creator is recognised; reflected in the Man, but governed by the degree that the man conforms to ‘God’s will’, i.e. the Good.

History tells that Duthac became Bishop of Tain, but we might want to examine this. His training in Ireland was entirely within the Celtic Christian tradition – one that would send missionaries out across Europe to found some of the most important centre of learning in history. It may have been that the Roman church tradition that drove Celtic Christianity back to Ireland, made Duthac, posthumously, into a bishop to show his historical conversion to the standard faith.

‘I saw the Holy City coming down from God out of Heaven, and he said unto me write’

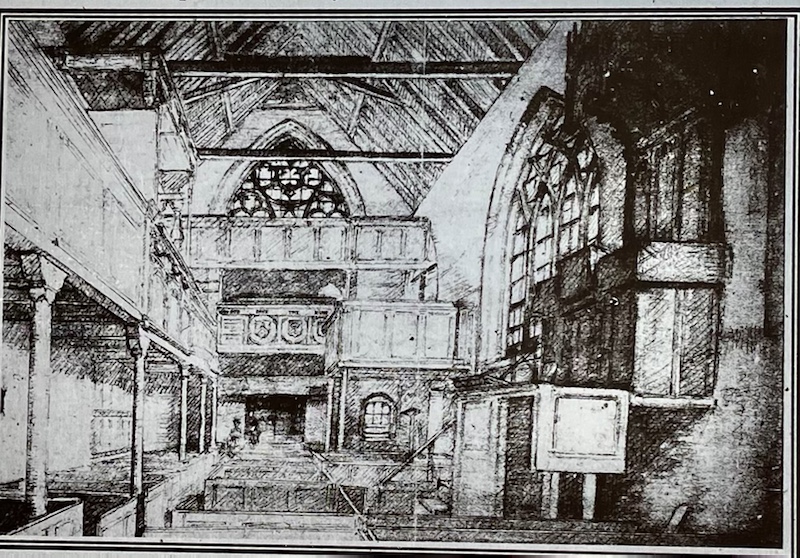

In the three previous posts, (see list at end of post) we have considered each of the buildings associated with St Duthac. The history of the later Memorial Church warrants further attention. During its time as the main church of Tain, it was a more complex building.

The black and white drawing, above, shows how the interior of the church once looked. Note the elevated ‘stalls’ on the left.

The construction and use of the north wall is curious. The above plan of 1815 shows separate exterior gallery stairs into the building. These gave direct entry to ‘lofts’ or galleries belonging to Tain’s trade guilds. The guilds oversaw apprenticeships and were the guarantor of the quality of work done by their craftsmen. They were a key part of the orderly government of the town, and linked strongly with the authority of the local church.

Tain is unique in Scotland in having an intact set of Guild ‘coats of arms’. These are displayed on the north wall of the St Duthac Memorial Church, just beneath the high window (below) containing the stained glass rendering of St Duthac, gazing up at the Citadel and the four letter of the Tetragrammaton (below). To my mind, a link is implied…

It would be appropriate to bring this series of posts to an end with a return to the mysterious stained glass window high in the north wall of the Memorial Church, (see images above and below) to consider if any of these last threads of mystery can be unified.

At the very top of the mysterious window over the Guild plaques, on the the dome of the ‘Citadel’ is written (left to right) something very special in Hebrew: Yod-Heh-Vav-Heh. It derives from ancient Hebrew wisdom and is an integral part of Kabbalistic teaching.

Its name of Tetragrammaton is the Hebrew ‘highest name of God’. Jewish scholars will not speak this name, as it is taken to be sacred, even though formed of four of the standard Hebrew letters of the alphabet.

We can safely assume that this is not a legacy of the Scottish Reformation. What, then, is it doing high on the north wall of the Memorial Church of St Duthac?

Western mysticism is not so silent on the subject, though the sanctity of the inner meaning of Tetragrammaton is preserved. In Kabbalistic teaching there are four ‘worlds’ of continuous creation which result in the ever unfolding ‘now’. Each of these worlds is represented by one of the four letters of Tetragrammaton.

This mysterious stained glass window was part of the 1870-1882 restoration of the church. The design and creation were carried out by James Ballantine and Sons, Edinburgh. Ballantine was a brilliant artist and, to me, it looks like he was given particular freeway with the style of this, window, which is nothing like the others.

There are other examples of the Tetragrammaton used in highly ceremonial church and cathedral buildings, such as Winchester Cathedral. Its use in so small a building as the St Duthac Memorial Church is extremely rare. I could be completely wrong, but I sense the presence of another protector of Duthac’s legacy, here – one that arose from the chasm of the Scottish Reformation that did everything possible to destroy the saint’s legacy – the Freemasons.

The Freemasons arose, mysteriously, after the Reformation. Early records were not kept in order to protect their members. They modelled themselves on a stonemason’s guild, but added their own origin myth. They prosper today and benefit from their own carefully-crafted rituals, and progressive degrees of learning. Their higher degrees contain detailed references to Kabbalistic learning, and the Tetragrammaton is an important symbol in this. I can only suggest that they may have been the sponsors of this very different window, and, by this act, ensured that the spirit of Duthac’s work was honoured into modern times and its potentially mystical nature not lost to history.

To this day, they are well known for their generosity in preserving key aspects of history in their respective Lodges.

There is no suggestion, here, that the spiritual world of St Duthac was related to that of the Freemasons. Duthac’s world was based on a teaching in Latin, not Hebrew. The ‘Celtic’ Christians of Ireland had a rich and sophisticated teaching method, based on an individual’s ‘sense of belonging’ with Christ. The Freemasons have a broader ‘church’, in which a man is urged to better himself through application and dedication to the highest principles ‘he’ can discover within himself. In that, they are related, but the Celtic Christian oath of having no luxury, not even that of travelling by anything other than foot, is very different from our modern notions of piety.

I am not a Freemason, but have admiration for their work.

Esoteric history is full of different, but related, systems of thought, each showing us a part of the inner wisdom in a form we can remember and use. There is no single system of teaching that has all the answers. Each has its own emphasis, based upon the teaching preferences of its founder(s).

The spiritual journey is personal. Others can help, but the excitement is in discovering that everything of real importance belongs to each of us, alone.

And that is a paradox… but the most beautiful one we will ever encounter.

The Silent Eye will return to the world of St Duthac via a modern ‘pilgrimage’ to be offered sometime in 2022, subject to possible Covid restrictions. We will follow a route (part walking, part driving, in stages) from the Black Isle, across the Cromarty Firth, and explore the Tarbat Peninsula, before finishing in Tain at the Pilgrimage Centre.

If you would like to be kept up to date with plans for this, you can register your interest at rivingtide@gmail.com

End of series.

Other posts in this series:

Part One, Part Two, Part Three. This is part Four.

©Stephen Tanham 2021

Stephen Tanham is a Director of the Silent Eye, a journey through the forest of personality to the dawn of Being.

Fascinating and insightful read, Steve. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Michael. I think the level of detail may have put a few people off. It was intriguing to follow the ‘trail’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Steve, I know what you mean, trying to pitch a blog just right for that imaginary reader. But I worry that sort of detailed “antiquarian” material isn’t being written any more, or rather it’s not being published in the traditional way, and if the knowledge wasn’t written up and preserved here, online, it never would be. I’m sure many other pilgrims will find it, and appreciate your efforts and your insights in time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Michael. That’s an interesting thought…

LikeLike

I loved the detail and intrigue, Steve. Thank you for putting it all together and sharing your insights. Fascinating read! (so, at least there’s one – two, including Michael – who hasn’t been put off! giggle)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Caroline! The numbers edged up during the day, but the length of such pieces can be a problem – and understandably so. People have busy lives. Glad you liked the trail of mystery. Michael is a stalwart, and we share a lot in terms of mystical perspective. Also, he comes from the same part of old Lancashire as me, so we’ve a certain degree of cultural history, though we’ve never met outside the online community.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating series, Steve. Thanks for researching, writing and sharing it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Sheri. Glad you enjoyed the journey.

LikeLiked by 1 person