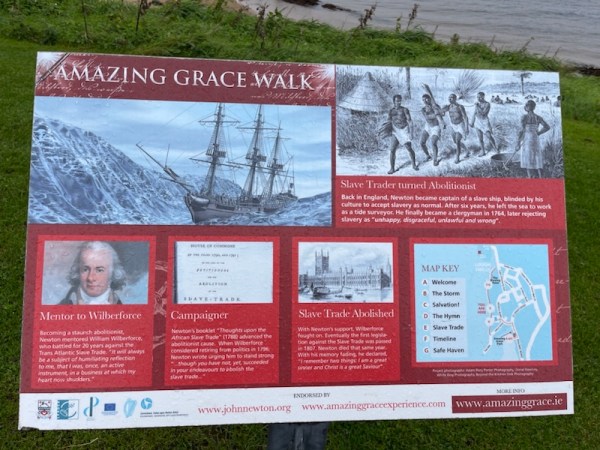

I’d never heard of John Newton, until, walking along the gardens that front the beach at Buncrana, County Donegal, we came across an information board describing his links to the town via the hymn ‘Amazing Grace’.

You may already have heard of this man, who could be described – at different times of his life – as both despicable and courageous.

Glancing at the tourist information, my immediate assumption was that Newton was a native of Donegal, and therefore celebrated, here, for his (eventual) dedication to the abolition of slavery. The latter was true, but he was born in Wapping in London, in 1725, the son of John Newton the elder, a shipmaster.

So what was Newton’s connection to this part of Donegal, one of the most beautiful and varied coastlines you could wish to experience? It takes a summary of his fascinating and eventful life to explain…

Following his mother’s death just before his seventh birthday, Newton was sent to spend two years at boarding school. At age eleven he went to sea for the first time with his father; subsequently sharing six voyages before his father retired in 1742.

Acting against his father’s wishes, he signed on with a merchant ship sailing to the Mediterranean.

In 1743, adrift from his father’s care, he was press-ganged into the Royal Navy, becoming a midshipman aboard HMS Horwich. He hated it, tried to desert and was publicly flogged, stripped to the waist and tied to a grating. He was reduced to the rank of common seaman.

He recovered, both physically and mentally, but his journal recalls how it hardened his nature…

Newton was introduced to the infamous ‘slave trade triangle’ of West Africa, America and Britain. Glimpsing a path to personal fortune, he rose to become a captain of several slave ships and, later, a substantial investor in the slave trade. At this stage of life, he seems to have accepted and embraced the ‘normality’ of the upper classes imposing slavery on ‘lesser beings’.

Later, and possibly part of this learning curve, he transferred to the Pegasus – a slave ship bound for West Africa. He had already established a reputation as outspoken, and was unpopular with the crew of the ship. In 1745 they left him in West Africa with a notorious slave trader – Amos Clowe. Clowe promptly gave him as a ‘slave’ to his native wife, Princess Paye, a woman who already owned many native slaves.

Newton later said of this period that he was ‘At once an infidel and libertine, a servant of of slaves in West Africa’. He refused to say much else about his incarceration.

‘At once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in West Africa’.

John Newton

Early in 1748, he was rescued by a sea captain who had been commissioned to find him by Newton’s father. He was returning to England on the merchant ship Greyhound, when it was caught in a terrible storm off the coast of Ireland. He awoke in his cabin to find the ship in distress and listing. In one report, he lashed himself to the untended wheel and stayed there through the days of storm that followed. During this, Newton began to pray and called out for ‘God’s mercy’. After a total of four weeks at sea, the Greyhound limped into Lough Swilly and came into dock at Bruncrana for repairs by a local shipwright.

It was the 10th March, 1748, a date he would mark as the start of his duty to God and fellow men and woman; a path he followed for the rest of his life as an evangelical Christian. He swore an oath to refrain from either gambling or profanity. He renounced alcohol, but continued to work in the slave trade, later saying that his conversion ‘to being a true believer took a number of years.’

Applying modern ‘standards’ of another age is problematic. But it struck me there was a degree of hypocrisy, here.

He returned to the sea and eventually captained three more ships before a stroke put an end to his seafaring career. By then his investments in slavery were considerable and he was secure. Since ‘being spared’ in the storm, he had longed to become a church minister, but found it difficult to gain sponsorship.

Moving to London in 1754, he took up the position of rector of St Mary’s Woolnoth Church and later contributed to the work of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, formed in 1787. He was one of only two evangelical clergymen in the whole of London, and, as good orator, was sought out by young and aspiring minds to develop their own arguments – often about the moral issues of slavery. He was a prolific writer, and published pamphlets espousing his causes.

He wrote: ‘So much light has been thrown upon the subject by many able pens, and so many respectable persons who have already engaged to use their utmost influence for the suppression of a traffic which contradicts the feelings of humanity, that it is hoped this stain of our national character will be wiped out’

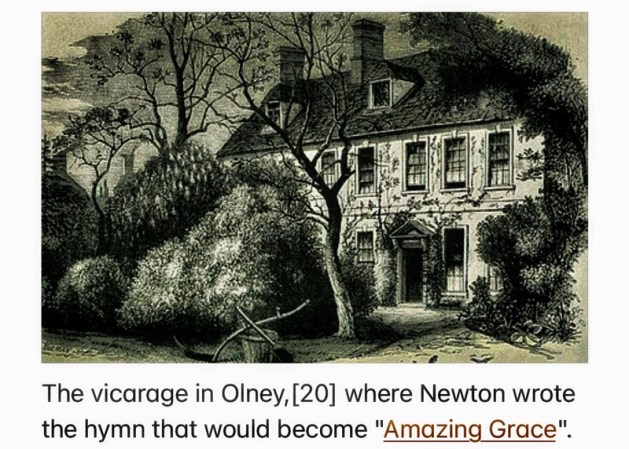

It took many years for him to be ordained as a priest for the parish of Olney, Buckinghamshire. There, in June 1764, he wrote the hymn that would become Amazing Grace. Later, the celebrated poet, William Cowper, worked with Newton on a volume of hymns published as Olney Hymns.

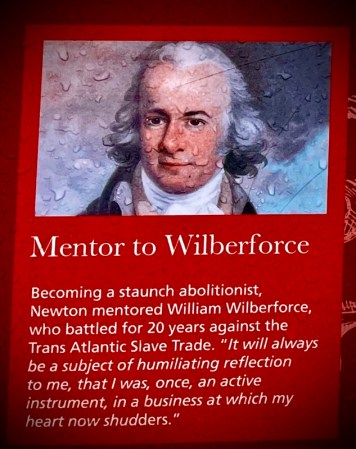

In London, the young William Wilberforce had become one of Newton’s intellectual circle. The now-clergyman and ex-ships’ master was able to give first-hand accounts of the appalling conditions in which slaves were transported and kept.

Newton saw in Wilberforce the presence in politics that he could not hope to attain. He supported the rising career of his new friend, and helped his resolve when the politician’s efforts seemed to be failing.

With Newton’s support, Wilberforce redoubled his political efforts, and the first legislation against the Slave Trade was passed in 1807. It would be decades before the full legislation was enacted, and only then because parliament agreed to recompense every slave-holder for their losses – a national debt that was only fully discharged in recent decades. But Wilberforce began the process, urged on by the ex-slaver who ‘found his living God’ in the waters of Co. Donegal.

Newton died that same year. With his memory fading, he declared “I remember two things; I am a great sinner and Christ is a great Saviour”

Is there a mystical perspective to such a vivid life? I believe so. We need to set aside the instant judgement that we tend to apply, based on modern moral consensus, and look at the ‘long curve’ of a person’s lifetime to see what their overall effect was. Newton, profiteer from the miseries of others’ suffering, became the informed strength that kept Wilberforce constant to his goal.

‘God moves in mysterious ways’ … and over long timescales. Our own existence is filled with opportunity; and that process may span the lives of many people joined in a unity of improvement for mankind. But the path of each will be unique and only found in the personal ‘now’.

We walked past the memorial to Newton on the next day. Knowing more about the man, and having begun this post, I could sense in the calm waters of Lough Swilly how he must have felt arriving, snatched from what seemed certain death, on this calm shore. We don’t often have monuments to ‘moments’, but this is a good one. Perhaps ‘moments’ more than men and women are what really power history; those times when something from a more causal dimension powers through the fabric of our space, time and event to ignite the waiting threads.

———-

Note: the photos of the environs of Lough Swilly are the work of the author.

———-

©Stephen Tanham 2023

Stephen Tanham is a writer, mystical teacher and Director of the Silent Eye, a correspondence-based journey through the forest of personality to the dawn of Being.

http://www.thesilenteye.co.uk and http://www.suningemini.blog

I’ve always been fascinated by the story of John Newton. Thanks for this informative post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Darlene. I’m glad it was informative. A complex man, I suspect!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some movies have been made about him. One was Amazing Grace in 2006 where Abert Finney plays John Newton.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll look out for it! Thanks, Darlene 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person