It was Easter Sunday, 20th April, 2025. Bernie had cooked us a fabulous Sunday lunch, now finished, leaving us relaxed and reflective. .

We had three guests; our longstanding friends and fellow dog-owners Siobhan and Paul, and a visiting new friend of theirs from New Zealand – Russ -who is pivotal to the rest of this true story.

Although you might have good reason for thinking that what follows is fiction…

The sun was shining and the air was warm. Russ and I went out into the garden with our drinks, leaving the others talking through the details of our forthcoming trip to Canada. We were to be reunited with the family in Toronto before visiting Ottawa and Montreal, ending our trip on a small island that was the home of L.M. Montgomery, the creator of the famous Anne of Green Gables novels.

Bernie remembers loving these books as a child. She hadn’t expected to be able to visit the place of their origin and setting: Prince Edward Island…

But it was shortly to come true.

Beyond books, this is a story of ancestors, and a great adventure undertaken by those ancestors. It’s quite a story, but it’s not our story. The people who follow in this true tale are not our ancestors. They are the ancestors of Russ and Paul – with Russ being a direct descendant of the main adventurer; a man we will shortly meet.

Here’s a photo of those whose story this is; Paul (leading) and Russ, the ‘Kiwi’ following behind. Both with ice creams in the Cornish sunshine – where the ancestral story, here, was uncovered.

Back to our garden and the post-lunch sojourn.

Russ is a keen gardener. We chatted about the difficulty of keeping on top of mowing the grass at that time of year, when the new life literally bursts forth with a very determined push.

Finishing his drink, Russ sat back, enjoying the sunshine. I assured him that Easter weather in England was seldom this kind.

We had been talking about travel and its joys and also how exhausting it can be.

“The problem with New Zealand,” he said. “Is how far away it is from anywhere else … except Australia!”

I chuckled in agreement. We had visited New Zealand a few years ago at the end of another Australian family reunion, followed by a short cruising holiday down the Australian coast from Sidney, via Melbourne and on through the Tasmin Straits. It is a beautiful place but very far away.

“Did Paul tell you about the family connection with New Zealand?”

“He did!” I smiled at the sheer courage of those – his ancestors – who had emigrated there.

“Did he say where they travelled from?”

I sipped the last of my wine. There was a quiet determination at work, here…

“From Prince Edward Island, off the Canadian east coast.” He half closed his eyes. “In a schooner, for heaven’s sake”.

My father had a modest sailing boat that he kept on Ullswater in the Lake District. It would sleep four people as long as they could cope with ‘camping’ under fibreglass. There was a toilet: ‘head’ in boatish, and a very small sink. We’re not talking posh…

Named Vogelsang – birdsong from German – it was my father’s pride and joy. It was moored in a small bay just off the northern shore of Ullswater, next to a rather snotty sailing club whose members always refused to have anything to do with us.

There’s much to learn about people from such encounters.

My girlfriend and I stayed on the boat one Easter holiday and practically froze to death. Each morning we had to break the ice on the hatch to get out to the deck, then row the dingy ashore to take an hour’s walk (we didn’t have a car) into Pooley Bridge where we’d try to find a warm coffee shop that was open. It was a frozen Easter.

Once there, we hoped the owner would take pity and let us eke out our meagre funds and stay in their lovely warmth.… for three very slow coffees.

Boats are seldom the objects of romance we might imagine!

And that was just a lake…

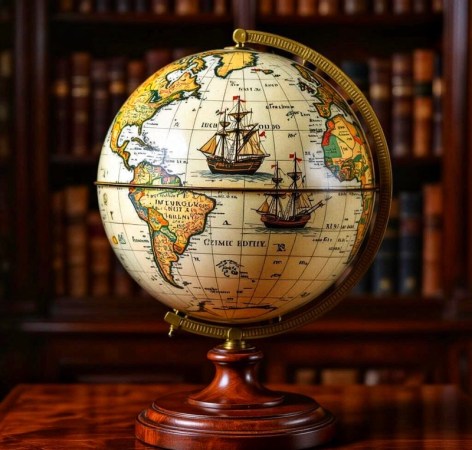

In my early twenties, I learned to sail Vogelsang by trial and error – often more of the latter. In the winters I used to read up on boating and ships. What Russ had just said surprised me: you would not normally choose a schooner – which, typically was used for offshore cargo between ports in the same country – to cross major oceans.

“A schooner?” I asked, looking into Russ’s smiling eyes. “All the way from Canada down across the Atlantic, under Africa and straight on across one-third of the planet to a barely-developed New Zealand?”

“Right…” he said, wistfully. “Or some similar ‘great circle’. It stopped me in my tracks, too; and we don’t even know the route they took … so far, we’ve found no further details of the voyage.” He leaned forward, laughing. “But we know what happened afterwards… And our family is at the end of that tree of descendants!”

Neither of us spoke for a while. I was trying to envisage the courage and skill such an adventure would have demanded.

Russ continued:

“With his family, a skipper they had hired…” he sipped the last of the juice, looking slightly theatrical. “And a cow.”

He waited for that to sink in.

“A cow?”

“Yes, so they could enjoy fresh milk as protein. They were resourceful people!”

I shook my head in wonder, and went quiet, trying to consider the logistics of putting that voyage together – and the slim chances of success.

“And they made it?”

“Yep,” Russ said. Just as they had made it from Bideford in Cornwall to Prince Edward Island in the first place!” He was lost in silent respect. “Took them 238 days.”

He let the import of that sink in. We were both quiet.

Bernie had seen us chatting away – this was the first time we had met Russ – and brought us fresh drinks. We sipped, deep in thought.

“And you found all this out in Cornwall.”

“We did…” Russ said. He took some more fruit juice. “Except for one important part.”

I chuckled, feeling that something key was about to be revealed. I said to Russ. “And?”

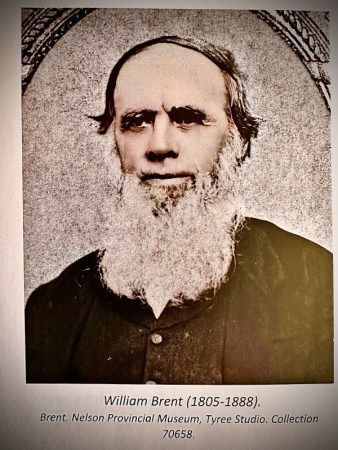

“Sadly we know little about Prince Edward Island – the place William Brent and his family had settled in after they left Cornwall; the place where his skills as a carpenter were put to full use and they prospered, the place where he had lived for over twenty-five years and raised a family.”

There was a sadness in his tone. “And I’m unlikely ever to be able to visit it.”

I had a feeling this might be our part in the story.

“But he eventually left Prince Edward Island? I asked. “Was there still a restless hunger?”

“None of us will ever know the background,” Russ said, staring into the blue sky of that lovely day. “But it may be linked to the fact that Prince Edward Island was becoming depleted of its once-abundant forests. Over-felling had decimated its tree population. William Brent may have had to make a decision: go back to England or carry on–‘

“-Around the planet!” I laughed. “What a brave soul he was!”

“They had the schooner built for them. Probably took most of their money. They took on a skipper, a first mate and a few deckhands, and set off across some of the Earth’s most dangerous seas…”

He sipped his orange juice, deep in thought. How could you not be! As fiction, it would be a fabulous story. As fact, it was astonishing.

“And they made it, intact?”

“Even the cow,” Russ said. “Sold the boat in New Zealand – which had always been the plan – and used the money to set themselves up there.”

“And they stayed?”

“Yes… Finally, William Brent had come to the end of his sailing adventures.”

“And now you know the whole story!”

“Not quite,” he said.

I leaned back, smiling.

“Prince Edward Island?” I ventured.

Russ laughed. “We’d love to know exactly where on Prince Edward Island the schooner was constructed. All we know is it was somewhere in St Mary’s Bay – which is a big area.”

“And we’re about to leave on a trip to Canada,” I said with a grin “culminating in Prince Edward Island…”

“Couldn’t make it up, could you!” Said Russ. “Just a few photos of the area would be great?”

And so our small part in this historical detective story emerged – willingly undertaken and quite an adventure in itself.

And a picture of Napoleon Bonaparte. What’s he doing here? Well… the story of why Prince Edward Island was vitally important to Britain is closely related to the actions of Napoleon. More in Wooden Ships, part two.

In one sense, that is the beginning and end of this barely believable tale, but there is so much more fascinating detail, about people, geography and lives, to tell.

I’ll try to set some of this background information down – in context- in the parts that follow, beginning in the second part – Wooden Ships (2).

©️Copyright Stephen Tanham, 2025. Photos by the author.

You can come to the memorial gardens within Kendal’s Maude’s Meadow either by Maude Street, which runs off the town centre, or by a dark and tree-overshadowed path from the old Quaker district of Fellside.

The latter is the best at this time of the early autumn. Much of the descending path is shrouded in venerable trees. If you’re lucky, upon entering the edge of the small park, your darkness-conditioned eyes will be met by the most wonderful circle of golden yellow – seeming to give off its own light.

I’m told by my wife that they are ‘black-eyed Susans’, otherwise know as Rudbeckia. A concentric disc of beauty, they surround the heart of the WW1 memorial here, to welcome everyone with the symbol of beauty and life emerging from the ruin of war.

©️Stephen Tanham, 2025. Photo by the author.

There is a circular walk around the hilltop that houses The Hoad monument to Sir John Barrow, at Ulverston, on the Cumbrian coast.

It was a perfect day – the epitome of summer. I spotted this view through the trees and loved it.

©️Stephen Tanham, 2025

+ #iphonephotography, #Photography,, #Silenti, #TravelwithaMysticalEye, Ancient Landscapes, landscapes, Travel and Photography

August comes to the Levens Estate

In August, a wonderful peacefulness descends on the estate around Levens Hall – the ancestral home of the Baggot family. The Levens Estate is a few miles south-west of the Cumbrian town of Kendal.

The recently upgraded cafe – with its large, open courtyard – makes for an ideal destination by car or, as with me and the Collie, on foot. Many people walk several miles to get there, restoring themselves at the cafe before reluctantly lacing the walking boots back up and setting off for home.

There’s another approach if you’re lucky enough to live relatively close. One person can walk the dog, the other leaving an hour later to join and collect the dog and its walker – via lunch.

We’re lucky enough to live an hour’s walk away. It’s the perfect dog walk, and just about at the limit of what our old Collie can manage these days. At ten years old, she is towards the end of the life expectations for the breed.

The first part of the walk crosses over the busy A590, the main feeder road from the M6 motorway into the heart of the Lake District. It’s good to be above and not in the flow of this hard-working road.

It’s worth noting that there is also a largely-unseen dimension of the terrain below the A590, which is also the crossing point of the River Kent just before it enters the Levens Estate and flows out into the top end of Morecambe Bay.

From the bridge – and staying on the quiet country lane, we come to a very tall stile that literally bestrides the sturdy stone wall of the Levens Park estate.

Dogs have to be on leads as there are deer. It is also the home of the unique Bagot Goats, named after the ancestral family who own the estate.

The first half-mile of the walk is a wide avenue between tall trees, with little variation. But soon the River Kent comes into view on the right-hand side and the path descends to meet it. This stretch is the most valued by photographers.

After a further twenty minutes’ walking we cross the busy A6. This used to be the main ‘trunk-road’ route between north-west England and Scotland, bridging the two with the notorious Shap Summit – one of highest stretches of road in England.

The huge ornamental gates of Levens Hall are dead ahead. Immediately after, we enter the grounds and seen the grand house on the left. The garden is one of the few surviving Tudor designs in the UK.

Tess has just about enough ‘puff’ to make this distance, and she enjoys a rest in the courtyard while we order a snack and a latté.

I hope you enjoyed the walk…

©️Copyright Stephen Tanham, 2025.

Photos by the author.

Returning from the south coast we saw signs to the Weald & Downland Living Museum. We didn’t have time to stop and explore it there and then but were able to return a few days later with Bernie’s relative from Haslemere.

We had a small lunch at the excellent cafe, then bought our tickets – not cheap at a shade under £18.00 each – and entered this large parkland set in the heart of the beautiful Sussex countryside.

The Weald and Downland Living Museum is located in the South Downs National Park in West Sussex, England. The museum features over 50 historic buildings dating from 950 AD to the 19th century.

The grassland site covers 40 acres and takes a good two hours to even stroll around. Stopping to investigate each building – most can be entered and explored – will double that time. We found the best approach was to highlight the most interesting and map out a route.

The cost of the tickets means you need to spend a reasonable time here to get the value. Three hours later, we emerged, tired but enriched with a much deeper knowledge of rural life in the past.

Here are a sample of the photos I took, together – where possible – with the matching description.

The Weald & Downland Living Museum offers a captivating journey through over 1,000 years of rural history in South East England.

This acclaimed open-air museum is a testament to the preservation of heritage, featuring more than 50 meticulously re-erected historic buildings saved from destruction across the region.

As you wander through its 40-acre site, you discover a living landscape where traditional trades and crafts are demonstrated daily, bringing the past vividly to life – such as ‘our daily bread’, below.

Among the museum’s major exhibits are:

- Bayleaf Farmhouse: A stunning 15th-century timber-framed Wealden hall house, offering a glimpse into early medieval domestic life.

- The Medieval Barn from Cowfold: Dating back to 1536, this impressive timber barn showcases agricultural practices of the late medieval period.

- Winkhurst Tudor Kitchen: An early 16th-century building that provides insight into Tudor-era cooking, brewing, and preserving.

- Market Hall from Titchfield: A striking public building that once served as a bustling hub of commerce.

- Aisled Barn from Hambrook: Built around 1771, this large barn with its distinctive aisle allowed wagons to easily enter for threshing and storage.

- Working Watermill and Bakery: Demonstrating traditional milling of flour and baking of bread, often available for visitors to sample.

- A fully working underground water supply with ‘village pump’.

- Victorian Schoolroom: A step back in time to the classrooms of the 18th and 19th centuries.

- The village has a working supply of pump-based fresh water.

- The museum also features a range of other fascinating structures, including cottages, workshops, and agricultural buildings, all set amidst period gardens and populated with rare-breed farm animals, offering an immersive historical experience.

We loved it. Three hours later and tired, we made our way back to the car. The other two occupants slept their way to our hosts home in Haslemere.

©️Stephen Tanham, 2025.

It’s busy on the beach at Bognor…

Not a line from a Music Hall song, as far as I know but it would have made a good one!

©️Stephen Tanham, 2025.

We stopped for a bite to eat at a specialist car seller based in a huge converted barn in the middle of beautiful Hampshire – long one of my favourite counties.

On the way back to the car this beautiful sky was above us. No words needed…

And for the fellow petrol-heads among us, here’s my pick of what was on offer in this fascinating motor emporium: a 1970s BMW CSL. The ‘L’ designated its construction from aluminium, endowing it with lightness and great strength.

Yours for a mere £140,000…

The world has moved on. I’ll stick to my electric car! But the trip down memory lane was fun! In my first computing job, my lady boss had one of these.

Quite…

©️Stephen Tanham, 2025.

Look at her…

This once-stray has now ruled our household for over ten years. The Collie – now well trained and subservient to her – knows its place..

It’s been a long battle but Misti is now working on me. My wife is not a morning person. The cat has figured this out, and has been refining her cat-terrorist skills as the summer progressed.

The problem with cats is that they are natively nocturnal – if they can be bothered. And, given a free paw, will exit the house to hunt all the interesting nightlife that passes through the garden.

The house is securely locked at night and we don’t believe in cat-flaps.

Hmmm purrs the cat… you can hear the devious cogs whirring.

Recently, I’ve noticed an increase in the Olympic long jumps off the windowsill with her landing on our resting bodies. But, as these have resulted in her being threatened with a holiday in the cattery, she has desisted.

Or rather, gone back to the drawing board.

I must have missed the prototypes, but at 04:17 this morning, Misti sailed through the bedroom air to land on the dog, who sleeps at the foot of the bed.

The dog became a howling fury of spinning claws on wood and headed for the door to the garden, ensuring I had to get up to avoid a poonami in the house.

Cat Billiards is a genius strategy.

She spent what was left of the night in the boiler room…

Anyone need a cat!

©️Stephen Tanham 2025.

There is a mysterious power about the number three. For some deep reason it is associated – in the human consciousness – with ‘completeness’.

Designers and gardeners will advise that you need an odd number of ‘arranged things’ to look good. The number one is exempt from this, as it, itself, is associated with unity – and not multiplicity, where the design considerations apply, therefore three is the first true odd number in a design sense.

In ancient spiritual thought, this is partly explained by ‘how things happen’. There is an initial impetus ‘to do’. This has to act on something, giving two entities. The result is a new state made by the combining nature of the two and taking the ‘whole’ onwards.

My photo, above, is hopefully a good example of such threeness. Taken in a local park, there are actually four ascending trunks from three trees: one of them has a double trunk.

The impact of the shot is the visual three-ness of the large beautiful trees that mark the exit of the park and the return to the tarmac beyond.

Like guardians, they wish us well – and urge us to return, soon; to refresh ourselves with their oxygen and symmetry.

©️Stephen Tanham, 2025

I did a short post on the striking ‘Setas de Sevilla’ back in February 2025, shortly after we returned from our Spanish city break. There was a lot of interest in that exotic structure in the sky and I promised to return with a fuller post – and some more photos.

Here it is…

Where is Seville?

Andalusia is an autonomous region, located on the Iberian Peninsula. It comprises eight provinces: Almería, Cádiz, Córdoba, Granada, Huelva, Jaén, Málaga, and Sevilla.

Seville is Andalusia’s capital city. Seville’s Spanish name is Sevilla, pron: Say-vee-ya) – a much more beautiful sound than the English version. If you say it correctly, local people smile back at you. It’s a rich experience.

Sevilla’s climate is beautiful in winter-spring, but can be ferociously hot in summer.

The story of the Setas de Sevilla…

In the spring of 2011 a strange structure began to rise above the busy La Encarnación Square.

The Setas de Sevilla (literally the Mushrooms of Seville) was not its original name. In the beginning, it was conceived as a giant parasol over the large and busy square, and named accordingly.

The original name was the Metropol Parasol, a giant wooden structure – the largest in the world – built as the centrepiece of the rejuvenation of one of the oldest quarters of the city.

It was created to operate as a dramatic but inviting ‘walkway-parasol’ upon which people could stroll along curving paths high above the streets. Aerial pathways would rise and fall, revealing different aspects of the city to those walking above. The whole experience would be nuanced by the journey of the bright ‘Spanish sun’ across the sky and the ever-changing light it cast.

The vision was delivered- magnificently. Just being there makes you tingle… Sunset is the most magical time.

The people of Seville continued to call it ‘the mushrooms’, so the wise city authorities went with the flow and agreed. It became Setas (mushrooms) de Sevilla: trips off the tongue and easy for us foreigners to remember… and what’s wrong with a mushroom, anyway!

The slow climb up the quite steep steps takes you to the entrance level. Tickets are purchased at a cost of approximately 16 euros. It’s well worth it, and – to the best of my knowledge – you can stay up there for as long as you wish.

Seville established a city-sponsored competition to choose a design for the Setas. 65 submissions were made. The winning design was by a German architect: Jürgen Mayer,

The new building was completed in April, 2011. It is 150 metres by 70, with an approximate height of 26 metres. Seeing it from below and walking around it on top, it seems to be a lot bigger.

The unique, wooden ‘parasols’ are made from an astonishing 3,500 cubic metres of micro-laminated Finnish pine. The building is certified and marked as the world’s largest wooden structure.

Creation of the Setas de Sevilla was not easy. There were technical problems as well as schedule delays. There were naming problems, too, as it was discovered that the architect had trademarked the name ‘Metropol Parasol’ and would charge for its use!

The town authorities reacted promptly, adopting the popular name the people used and Setas de Sevilla became the building’s official name.

Since its opening, the Setas de Sevilla has become the city’s third-most visited site in the city.

If you are ever close, make the trip and experience it. It’s an exciting and very ‘happy’ place. But then, sunshine tends to do that to people!

©️Stephen Tanham. Photos by the author.

You must be logged in to post a comment.