The wind howled at us as we left the car park to climb the hill to the strange stone ring on its summit. It’s in the Republic of Ireland, near the border with Northern Ireland; all of it within the ancient province of Ulster.

Bernie had seen it in a guide book and we wanted to take a look while we were in the area.

By the time we approached the large stone structure, the gale was actively trying to blow us back down… Donegal weather is not boring!

This dark and – on this day – forbidding destination is named Grianan of Aileach, and it has an illustrious history that is believed to have begun in the 6th century, CE.

From the site of the ring, you can see practically everything in the neighbouring landscape of sister hills and a vast amount of water.

My immediate impression was of a similarity to Glastonbury Tor, which is much more celebrated, but has a similar (to me) ‘self-contained’ feel..

In an emotional sense – and there was a lot of it up there – you can feel the hill’s suitability for seeing what lies below it – and, I suspect, above it, too. This has a dimension that is not simply physical.

The wall is about 4.5 metres (15 ft) thick and 5 metres (16 ft) high. Inside it has three terraces, which are linked by steps, and two long passages within that. Originally, there would have been buildings inside the ringfort. Just outside it are the remains of a well and a tumulus.

The main structure of the stone ring is five metres high and visible for miles around.

It is undoubtedly ancient. There is evidence that the site had been in use before the fort was built. It has been identified as the seat of the Kingdom of Ailech and one of the royal sites of Gaelic Ireland.

The place-name Aileach means a rocky place. The amount of rock used in its construction becomes apparent from the multiple layers of the interior. This was created with a huge amount of effort.

Ancient History:

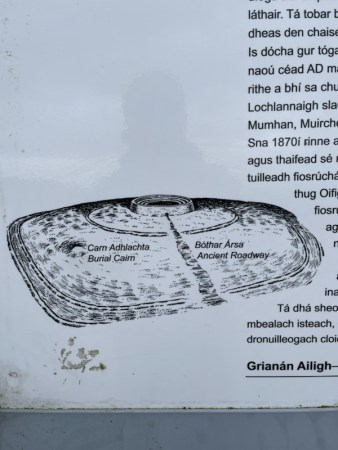

Evidence for an earlier prehistoric hillfort survives at the site in the form of three, low banks or ramparts and ditches which enclose the stone fort.

An ancient roadway ran up to the site (see above). There is a holy well, dedicated to St Patrick to the south of the stone fort and the site of a burial cairn to the east.

The stone fort (also known as a cashel) as we see it today was probably constructed in the late eighth or early ninth century CE as the capital of the Cenel n Eogain, the Kings of this part of Ulster.

In 904 and 939 Aileach was plundered by the Vikings. The final destruction of the original fort was carried out in 1101 by the army of Jar Muirchertach Ua Briain, King of Munster.

By the 12th century, the Kingdom of Ailech had become embattled and had lost substantial territory to the invading Normans. According to Irish literature, the ring-fort was mostly destroyed by the then King of Münster, Muirchertach Ua Briain. Substantial restoration work was undertaken in 1870. Today, the site is protected as an Irish National Monument.

In the 1870’s the cashel was restored by Dr Walter Bernard of Derry who recorded the finding of stone objects. In 2001 there were further archaeological and engineering investigations prior to an intensive conservation project.

These uncovered glass, pottery and clay pipe fragments dating from the nineteenth century works, but no other remains.

The lintel-covered entrance in the cashel leads into an interior enclosed by a wall that rises in three terraces and is accessible by inset stairways.

Within the wall are two wall chambers which stop short of the entrance. In 1935 the archeologist George Petrie recorded a rectangular stone building in the centre which is no longer standing.

A social history?

I’m no expert in hill-forts. I do, though, have a keen sense of ‘feel’ for a place. When we were walking up the hill towards what was simply a ‘ring of stone’ on the summit, I felt a mix of impressions.

There was ‘security’ here, but upon entering, there was a sense of ‘meeting and community’. One could imagine a gathering of tribes, perhaps? Maybe even some commerce in the form of a market outside the walls.

Such sites are seldom without ritual significance. The top of a hill opens up the sky and the parade of seasonal events, including the all -important equinoxes and solstices by which the cycles of all life were calibrated and ‘seen-felt’ to have their different living qualities.

The ancients extended their sense of ‘self’ deeply into the landscape. What we view dispassionately as objects were seen to have qualities derived from life, and attributed, in modified form, to all of the ‘world’ around them. To use other language, the ‘out-there’ was not seen as a separate domain to their ‘in-here’.

When they did gather, they carried this openness to the ‘out there’ with them, which makes places of ancient ritual so rich in potential for our own communion with the natural world.

None of this takes away from our rational and scientific skills; they are simply different perspectives on the same world. They lived in an age of qualities; we inhabit an age of quantity.

Source Notes: Grianán of Aileach. Abandoned. 12th century CE. Periods. Iron Age–Middle Ages. Cultures. Gaelic. Associated with. Kings of Ailech. Site notes Excavation dates. 1830s; 1870s. Archaeologists George Petrie; Walter Bernard

———-

©Stephen Tanham 2023

Stephen Tanham is a writer, mystical teacher and Director of the Silent Eye, a correspondence-based journey through the forest of personality to the dawn of Being.

http://www.thesilenteye.co.uk and http://www.suningemini.blog

This place is fascinating. Like you, I found Ireland to be a mystical place with a strong connection to the past.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. I felt it was an easy landscape to ‘open yourself’ to. Very peaceful, now, despite its long history of bloodshed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a stunning site, Steve. I’ve not heard of this before. Fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Michael. If you’ve not been to Co Donegal, put it on your list. It’s an impressive place!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I shall, Steve. The west of Ireland has been on my list for too long.

LikeLiked by 1 person